The Lancet Psychiatry

February, March & April 2020 covers

In autumn 2019 I was approached by my gallery, Bethlem Gallery, to see if I was interested in a working collaboration with The Lancet Psychiatry. The relationship would be to provide imagery for 11 of the journal’s covers throughout 2020. I was really excited from the start and slowly we began to have discussions about the curatorial process of selecting the imagery.

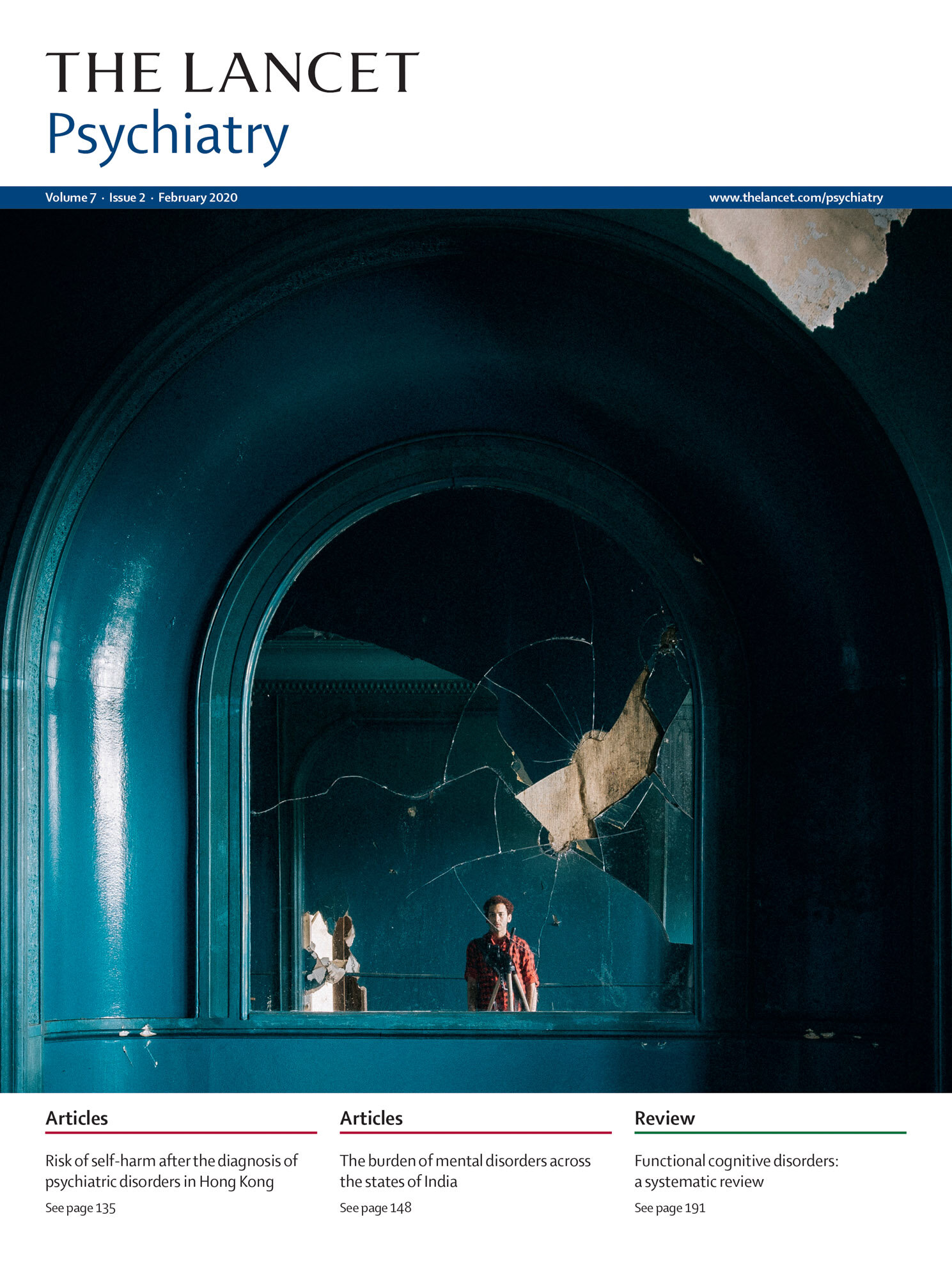

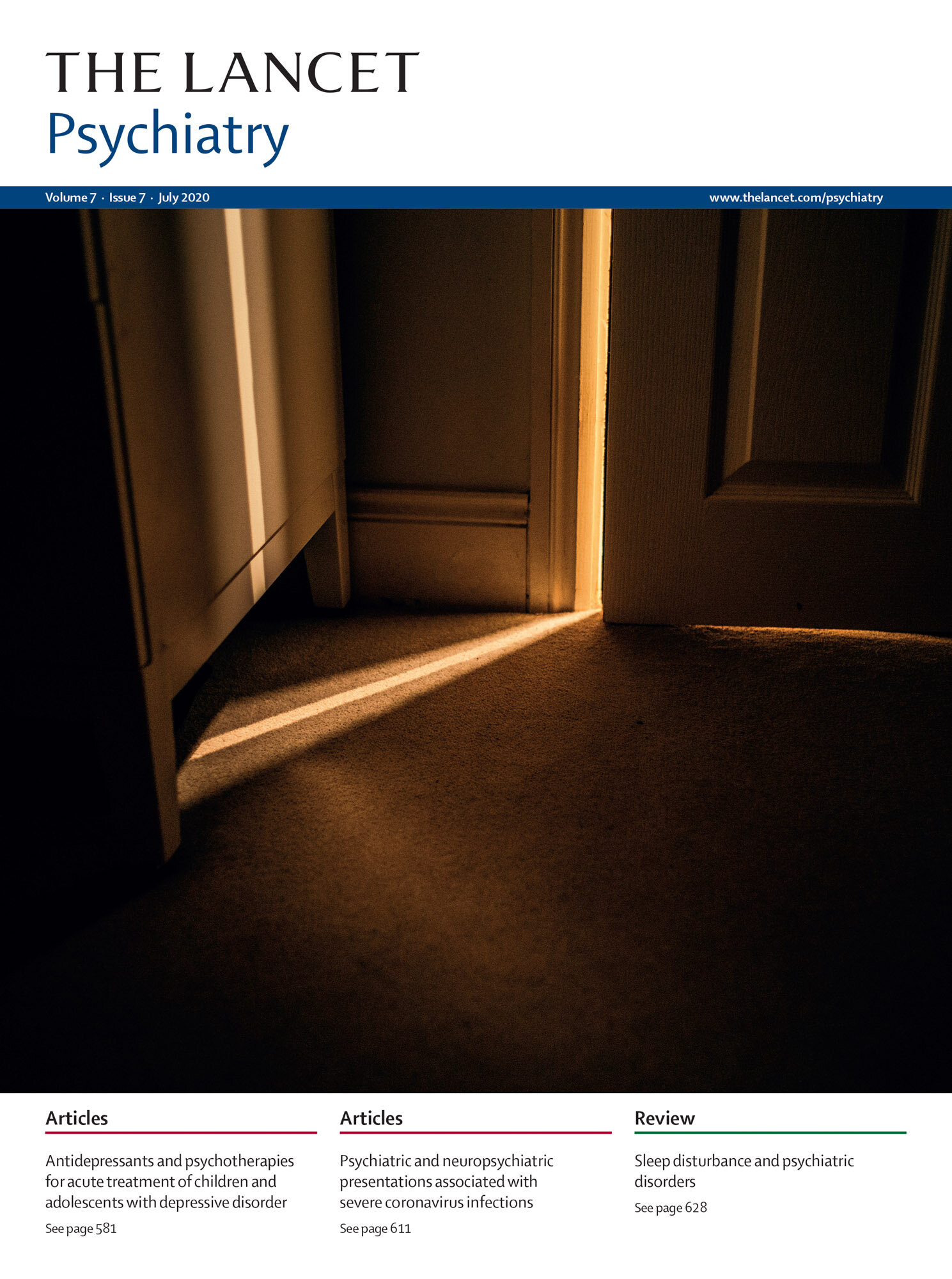

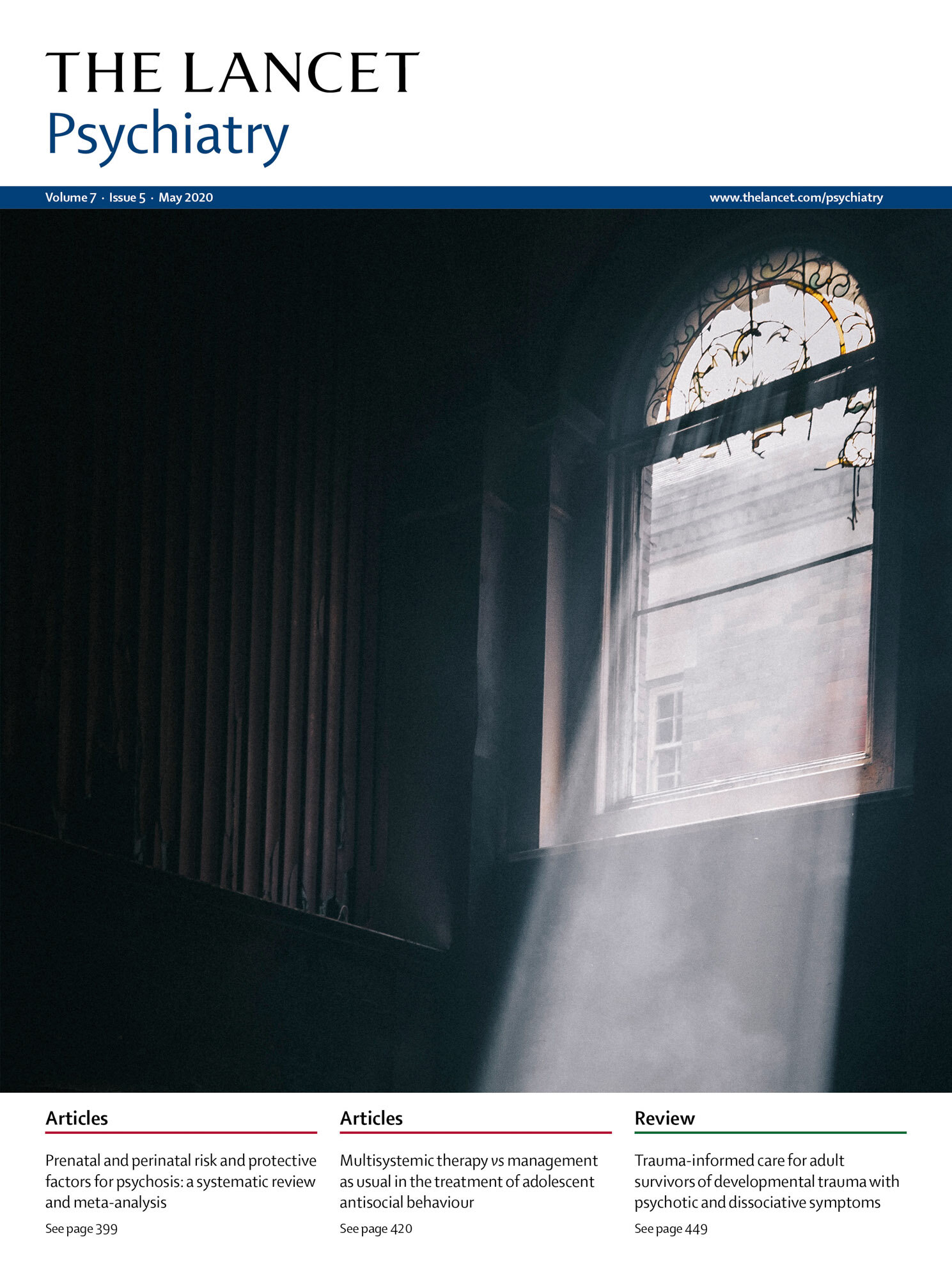

Niall Boyce, Editor in Chief, had noted the themes of windows, doors, frames and reflections in my work, and it automatically took me back to some of my earliest work from my project Abandoned. What was so great about the entire curatorial process was that it was a conversation between Niall and I, and we were able to develop a series of images that appealed to both of us, using his initial ideas as the catalyst. I am often wary of curating works from such a broad theme, particularly with someone I have never met, but the entire process felt very easy.

The Lancet Psychiatry is one of the world’s leading academic journals on psychiatry. The Lancet itself was started in 1823 and now encompasses 19 medical journals on a range of topics from HIV to Planetary Health. When Bethlem Gallery first approached me I knew a bit about what The Lancet did, but it hadn’t factored into my world that I would ever be working with The Lancet. It felt quite exciting.

My history with psychiatry has not been all roses. It also hasn’t been entirely awful. I’m aware that many of my friends and colleagues often fall on the side of pro or anti-psychiatry and I always feel that I am neither one or the other. I have had both positive and negative experiences in psychiatry. These are situations I have always put down to personal interactions with individuals rather than the field of psychiatry. I should say I am only commenting on my own experience here, not for anyone else. I am also not singing the praises or the field or condemning it.

My interaction with psychiatry started in my early teens and takes me through to the present day in my 30s. From taking psychotropic medication (awful) to going through a number of psychotherapy programmes (mixture of fantastic and awful), some of it has been helpful, some of it not so helpful. That is both the field of psychiatry and the people delivering it. I have experienced incredibly disempowering experiences and also some experiences with people that will stay with me forever, having changed the way I think, feel and act.

I’ve had a number of turning points that really emphasised the support that I could experience in psychiatry. In 2004 I was in a psychiatric hospital in Sussex after trying to take my own life. Each interaction I had with psychiatric staff seemed completely different. I remember talking to a nurse administering my medication who seemed to have no interest in talking to me. Yet there was a profound experience that will stay with me forever. After my partner had left one evening, a psychiatric nurse sat on my bed and listened to me talk about what was going on in my life. He would gently guide the conversation but primarily listened, nodding supportively. He did not try to solve my problems or rescue me, but provided me with the space to feel heard, acknowledged and without judgement. It was this experience that led me to volunteer and work with Maytree on our photography project I Want to Live so many years later.

Another experience is when I was around 23 and in the midst of a breakdown. Due to a number of awful circumstances I was struggling and was clearly suicidal. I was seeing a psychiatrist regularly who made a real point of not telling me how I felt and what my problems were, but asking me what they were. She was the first psychiatrist to ask me what I thought my diagnosis might be. I was scared to tell her, and for good reason. Previously when I had mentioned a diagnosis I was scorned and told I was not able to recognise my own difficulties. She was supportive, engaging and worked in a collaborative way to allow me to feel empowered to have an informed opinion of my difficulties. I was made to feel like the expert by experience in the room. After all, if I’m not the expert in reporting my own experiences, who is?

Psychiatry is such an enormous and complex subject, especially weighted by your experiences as a patient. I am not passing judgement here on whether psychiatry works and how it works, but just commenting from my own experience and how it is intertwined with my arts practice. What was strange for me, as I saw that first cover, is the sudden distilled essence of time and progression for me. To once see myself as a vulnerable boy who saw no future and could not see himself living to the age of 30, whilst engaging in psychiatric services, to somehow seeing himself on the cover of The Lancet Psychiatry aged 35 (albeit still involved with services) has been quite baffling to me.

Some of the work that will feature on the covers are from my photographic visual diaries, something that I started in my teens as a way to navigate the difficulties I had in talking about or recognising how I felt. I have used this practice as a way to document the world around me, but to also connect to intangible feelings and thoughts that I still struggle to verbalise. These works, much like all of my personal works (not commissions) are made without the intention to share, to be seen, or judged. They are imperative to my decoding of the world and maintaining a sense of routine and creative outlet.

Creating these images as a practice, as a way to navigate the world, is easy. It’s easy because it’s something that I love to do and do without expectation of money, praise or prestige. The thing about making as a means to process is that it can take you to strange places years if not decades later. It’s therefore quite a surprise when opportunities pop up, like the Lancet opportunity, to share these deeply personal works. It breathes life into the experiences of creating them again and again, with scope for further reflection in hindsight. This opportunity has highlighted just how far I’ve come.